Dodwell: The Obliquity of the Ecliptic

CHAPTER 10 THE GREAT PERUVIAN SOLAR TEMPLE OF TIAHUANACO

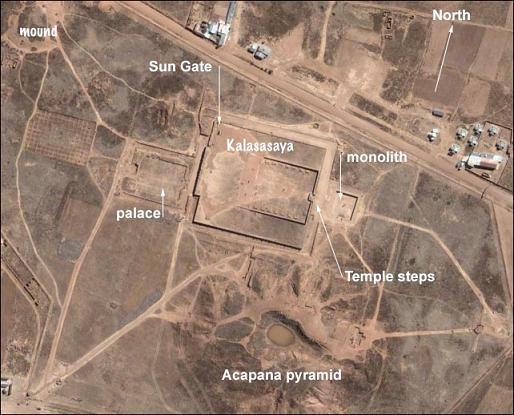

http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/tiahuanaco/tiahuanaco.gif The information available concerning this remarkable ancient Solar Temple is not so complete as in the case of Karnak and Stonehenge, but so far as it goes, it indicates a date of construction in agreement with the new Curve of Obliquity rather than with Newcomb’s Curve. This Temple of the Sun is described in many books on Peru. The ruins are situated in the high mountains about 13 miles from the Southern end of Lake Titicaca, and about 43 miles West from La Paz, the capital city of Bolivia. Their geographical position is: Longitude 68° 50’ West of Greenwich; Latitude 16 ° 34.9’ South; height above sea level, 12,615 feet.

http://www.bibliotecapleyades.net/imagenes/tiahuanaco_mapa_3.jpg During the years 1928-1929, a detailed study of the Temple with careful measurements was made by Dr. Rolf Müller,(1) of the Potsdam Observatory, in an attempt to arrive at an astronomical determination of its age, following on an earlier attempt made by Dr. Posnansky in 1912. Dr. Müller shows that, without the slightest doubt, this Temple was constructed and used for the definite purpose, among other things, of observing the sun at sunrise at the Summer and Winter solstices, as well as at the equinoxes, in connection with the Peruvian calendar. As A.H. Verrill says in Old Civilizations of the New World,

After describing the great procession of the Inca with his attendants from the palace to the place where the summer solstitial sunrise was observed, he says,

Dr. Müller shows in his work that the dimensions of the Temple of Tiahuanaco were chosen in such a way that from a point near the centre of the Western wall the stone pillar at the South-East corner marked the position of the summer solstitial sunrise in ancient times, due allowance being made for refraction and altitude of the horizon at the sunrise point; similarly, from the same point of observation, the outermost stone pillar at the North-East corner of the Temple marked the point of sunrise at the Winter solstice. Dr. Müller suggests, also, that several pillars, projecting outwards on the Western side of the Temple, were used for observations of the moon from a great stone block near the centre of the Temple, which has, however, been split in halves, and is displaced from its original position. However this may be, there can be no doubt that observations were made in this Temple of the sun at the solstices and equinoxes. The Temple is 422 ½ feet from East to West and 388 feet from North to South. Practically all the transportable material has been removed, first by the Spanish conquerors of Peru from the time of Pizarro for church building, and later “by modern vandals, especially the builders of the Guiqui-La Paz Railway, who it is stated have taken away within the past ten years (1919-1929) more than 500 train loads of stone for building its bridges and warehouses.” Thus all that now remains of the original building is a kind of Peruvian Stonehenge of great upright monoliths together with a beautifully carved monolithic stone door of the sun near the North-Western corner and a great stone stairway on the Eastern side.

The Sun Gate Dr. Müller assumes that, at the time when the Temple was constructed, the observation point of the Summer Solstitial sunrise was in the centre of the Western wall, but this gives an impossible date, 15,000 B.C., for the date of construction. However, it is significant that, in the exact centre line of the building, and at a distance of 17 feet 9 inches from the centre of the West wall toward the middle of the building, there is a large isolated flat block of stone lying on the ground, 9 feet in length, and 6 feet 9 inches in width, which exactly fulfills the necessary conditions. It seems probable that this was the actual site from which the observations of the rising sun were made both at the solstices and at the equinoxes. This great flat stone, which suggests a similarity with the Altar Stone of Stonehenge, has been fully exposed by excavation. Its unique position in the building, and its distance from the South-East and North-East corner stones of the Temple, correspond fully with the astronomical requirements for the observation of sunrise at the Summer and Winter solstices, which, it is clear, were carried out at this Temple. Dr. Müller made observations from three points in the Temple, near the centre of the West Wall, relating to the position of the sun at sunrise at the summer and winter solstices. The observations were referred to the centre of the sun, as it appeared on the visible horizon, at the two solstitial points. The height of the horizon was measured, and corrections for refraction were applied from a table of refractions, calculated for the altitude of Tiahuanaco, and supplied by Professor Harzer of Kiel. The three points of observation were (W) centre of West Wall; (I) a point inside the Temple, 1.8 metres (5 feet 11 inches) from W; and (S) centre of Stone Block, 5.4 metres (17 feet 9 inches) from W. [from the Setterfields: any diagram originally intended for this manuscript has, to the best of our knowledge, been lost. The following photo and caption is from the location listed below it on the internet.]

http://imagenes.mailxmail.com/cursos/imagenes/1/4/tiahuanaco-1-2_24341_17_1.JPG Dr. Müller, standing at the point I, observed the sun at solstitial sunrise exactly over the centre of the corner pillars A and B respectively. The angle AIB thus gave the total amplitude referred to the solstices of 1930. From the point W (centre of West wall), the measured angle AWB corresponds to the total amplitude at an epoch when an observer, standing at the point W would see the solstitial sunrise at A and B respectively. From the point S (centre of Stone Block), the measured angle ASB corresponds to the total amplitude at an epoch when an observer, standing at the point S. would see the solstitial sunrise at A and B respectively. The results of these observations and measurements are given in the following table

The solstitial declination of the sun corresponding to these observations, and the dates in agreement with these values of the declination, are shown in the following table

The date 15,000 B.C. is not historically admissible. The above results therefore indicate the probability that the great flat stone block, S., was the actual Sunrise Observation Stone, from which, year by year, the solstitial sunrise positions were observed, for the purposes of the Peruvian calendar, and for the ceremonies of Sun worship. It should perhaps be noted that the actual positions of the sun on the horizon would be the points observed, and the corner stones would be used as indicators of these points. In the illustration, the top of the distant South-East corner stone is below the horizon from the point from which the photograph was taken, and the rising sun, at the Summer (December) solstice, would be seen at a small elevation above the corner stone. In the course of time, as the sun’s solstitial declination decreased, a slight change of position of the observer from the centre of the flat Stone Block would be sufficient to keep the top of the corner stone in coincidence with the observed sunrise point on the horizon. Adopting the conclusion that when the Temple was built, the centre of the flat Stone Block was the point from which the observations of mid-summer and mid-winter sunrises were made, the date of construction, in accordance with Newcomb’s Formula would be about 4000 B.C., but by the New Curve it would be about 700 B.C. There are other interesting astronomical features in the Solar Temple of Tiahuanaco, which deserve further investigations, particularly in regard to the use of the other great flat Stone which Dr. Müller calls the “Observation Stone,” near the centre of the Temple. This is an unsymmetrical position, however, and is split in halves, so that possibly it is not quite in its original position. (Dr. Müller says, “It is conceivable that an extension southwards of the Stone was intended to be laid, or was even in existence.”) It is difficult therefore to draw any reliable conclusions from observations made from the centre of this Stone, either to the eastern corner stones of the inner “Sanctuary” for sunrise observations, or to the western corner stones of the later Tiahuanaco II construction on the western side of the main building. The principle astronomical data of the Temple as already set out, however, are more satisfactory. If it is admitted that the flat Stone Block, S, was in all probability the point from which the solstitial sunrises were originally observed, we may now test the approximate date of construction, found astronomically, with that which is derived from the best modern archaeological results. The Archaeological Date of Tiahuanaco An immense amount of material is available for estimating the chronology of the civilizations which have flourished in the region of the Andes. Dr. Philip Ainsworth Means, in his great study of this subject, entitled Ancient Civilisations of the Andes (1931), gives a list of 629 works which he has consulted and used. He shows that there is a striking parallelism between the cultural development of the Mayas and other peoples of Mexico and Central America, and that of the Peruvians. The earliest people of Peru came from the north, both by land and by sea, and they settled on the coast of Peru and in the adjacent high mountainous regions of the Andes. Their first arrival in Peru probably took place many centuries before the Christian Era. In common with the Mayas, they were remarkable for their magnificent civilizations, lofty temples, great cities and towns, now represented by vast ruins of cyclopean buildings. In some cases, as at the Solar Temple of Tiahuanaco, great building stones, weighing up to 60 or 70 tons, are mentioned. A comparison of the respective achievements and history of these nations, as far as they can be traced, is essential in forming a reliable estimate of the date at which the various developments, in particular the building of the Temple of Tiahuanaco, occurred. This is well shown in the following tabular and historical comparisons, given by Dr. Means.

Central American and Andean Cultural History Compared (on a basis of native data recoverd by modern research) from Ancient Civilisations of the Andes, by Philip Ainsworth Means, Charles Scribners Son 1931, p. 47 [note: the original formatting was not reproducible here, but the information is as follows]

1824 on -- End of Spanish Occupation -- Yucatan and Peru independent

Cultural Periods in the Andean Area as Shown by Modern Research into folk Memory and by Archaeology from Ancient Civilisations of the Andes, by Philip Ainsworth Means, Charles Scribners Son 1931, pp. 48-49

A similar comparison between the Maya civilization and that of the Peruvians is available from other sources. S.G. Morley, in the National Geographic Magazine, January 1925, gives a concise account of early Maya history. Peruvian history shows a remarkable similarity with that of the Mayas, both in periods of expansion and decline, and in cultural characteristics. General conclusions, based on these archaeological studies, make it highly probable that the building of the great Solar Temple of Tiahuanaco in the Tiahuanaco I period took place at some time during the first millennium before the Christian Era. C.R. Enock, in The Secret of the Pacific (1912, p. 169) says “The temples and fortresses of Cuzco date only from the eleventh century, or later, of the Christian era, when the Inca dynasty came into being; those of Tiahuanaco are of unknown age, and doubtless were built by the Aymaras at the time of their greatest culture before their overthrow, or even predecessors of those people. Some writers, indeed, have maintained that they were contemporaneous with Babylon or Assyria.” This would probably put the date somewhere between 800 B.C. and 600 B.C. In view of the formidable array of archaeological documents and evidence presented by Dr. Means, it seems wholly impossible to put the building of the Solar Temple of Tiahuanaco so far back as 4000 B.C. Thus, although the astronomical and archaeological results for Tiahuanaco are not so precise as in the case of Karnak or Stonehenge, there is, nevertheless, a strong indication that the date of construction is in agreement with the new Curve of Obliquity rather than with Newcomb’s Curve. Attention is drawn to this ancient Solar Temple, not only because it probably gives support to the New Curve of Obliquity, but also because it is an interesting case for further investigation, from the point of view of both astronomy and archaeology.

http://www.m-koch.ch/Travel/peru-bolivia/IMG_1291.JPG _________________

|