Pyramids and the behavior of the universeBarry Setterfield; February, 2021

Dating the Pyramids: On the 16th December 2020, the BBC published an article based on an archaeological discovery. In 1946, some wood which had been used in the construction of the Great Pyramid was tagged by archaeologists and donated to Aberdeen University. It was then misplaced. However, it was recently found, and then atomically dated. The atomic date lies between 3341 and 3094 BC, with an average date of about 3217 BC. However, as noted by Baines and Malek in “Ancient Egypt,” the actual historical construction date is close to 2550 BC. This is figured via Egyptian recorded history and events. That date accords with celestial phenomena, which includes the way the pyramids were precisely aligned north-south and east-west to within a few minutes of arc. (60 minutes of arc equals one degree, and 360 degrees equals one circle). Today we could use the Pole Star (the North Star) to achieve this type of accuracy. But because of something called ‘precession,’ our north pole points at a different part of the sky at different times. That means that Polaris, our “North Star,” would not have been pointing north in 2550 BC. Instead, by hanging a plumb line on scaffolding and waiting until two designated stars in Ursa Major and Ursa Minor were vertically aligned on the plumb-line, the ancients could find true north. Because several different star alignments were possible find true north, this method would work for just over a century either side of 2467 BC. Thus, 2550 BC was about the prime time that method would work without the alignment being skewed. This works in well with other data and tends to confirm the standard historical dating, as mentioned by Baines and Malek. A Scriptural Witness: A number of biblical scholars dispute this date on the basis of our current Old Testament chronologies. These chronologies are the result of the Masoretic text, established about 100 AD. However, the 2550 BC date is in very close agreement with the earliest translation of the Old Testament, the Septuagint, or LXX, done in Alexandria in 282 BC. This translation was from the original paleo-Hebrew into Greek. This translation of the whole Tanach into Greek was held in high regard by the Jews, since Greek was the common trading language of that time, understood by everyone in the Eastern Mediterranean. Having their Scriptures in Greek resulted the spread of synagogues around the eastern Mediterranean -- gathering places for the Jewish Scriptures to be read. The Eastern Orthodox churches still retain this version of the Old Testament. Importantly, this ancient chronology also fits in with Assyrian, Sumerian and Akkadian historical chronologies, as well as the dating of the pyramids. Furthermore, the chronology referenced in the writings of the early Church Fathers from about 100 AD to 300 AD also supports these dates, as do the early works of the Jewish historian, Josephus. So, in addition to Egyptian history and celestial phenomena, we have a Scriptural witness, and that of the first Church fathers and a Jewish historian, that the 2550 BC date of pyramid construction is approximately correct. Discrepant Dates: The problem is that, if this date is correct, then, as the 2020 article states, there is a discrepancy of about 500 years or more between the historical date and the atomic date regarding pyramid construction. Several years earlier, this discrepancy had been noticed in an analysis of atomic dates by the David H. Koch Pyramid Project published in Archaeology, 52 (5), Sept/Oct 1999. Their 1984 data indicated an atomic age which averaged 374 years older than the historical dates for the period from Dynasty 3 to Dynasty 5 (Khufu built his pyramid in Dynasty 4). Eleven years later, their 1995 study gave results from 1st to 6th Dynasty material which ranged from only 100 to 350 years older than historical data. An additional problem was that the atomic dates were rather scattered, even within a single monument. This means that this group of dates were less consistent than the 1984 study, but nevertheless indicated that atomic dates were up to 350 years older than historical dates. This was supported by Bonani et al., whose 2001 analysis suggested this dating discrepancy held throughout much of the Old Kingdom period in Egypt [Radiocarbon 43 (3), pp.1297 ff (May 2001)]. As it stands, the atomic dates give consistently older results than historical data, ranging from 300 to over 500 years older. However, the most recent and accurate data (from the 2020 BBC article referenced at the beginning) shows an even larger average difference of 667 years. An Ongoing Debate: The discrepancy has led to debate. Does the problem lie in misleading chronological records affecting the true historical date, or perhaps in the atomic processes themselves, or even, simply, because they used some very old wood. This last option has been favored by some archaeologists, who say that early clearing of timber left the region denuded of wood by the time the pyramids were built. Thus, old wood had to be recycled and repurposed for pyramid construction. On the other hand, many creationists say that the early biblical texts from around 282 BC give dates which are in error, and that only the Masoretic text originating with Rabbi Akiba’s council around 100 AD is reliable. This means those creationists even call into question historical data. They also discount all forms of radiometric dating, including that used for these artefacts. Thus, they dismiss both the historical dates and the atomic dates, persisting with the chronology which originated with Rabbi Akiba’s group. Because Akiba had an agenda to push, this may be giving undue credence to his version of the scriptures and it chronology. We have discussed this matter in detail in several places including here: https://www.barrysetterfield.org/Septuagint_History.html#Jamnia Many creationists like to dismiss all atomic, or radiometric, dating in totality. Atomic dating does run into a problem, but not for the reasons so many of those creationists state. Instead, these pyramid data help provide an understanding of why atomic dates generally have the trends that these archaeologists have uncovered. Let us examine the situation in more detail.

Atomic Behavior: All forms of atomic dating, including radiometric dating, depend on the behavior of an atom or atoms or some atomic process. Atoms are made up of a nucleus with positively charged particles (protons) and usually some neutrons, which are electrically neutral. This positively charged nucleus is then surrounded by negatively charged electrons in orbitals or shells. The number of electrons usually just balances the number of positive charges in the nucleus, so the atom is electrically neutral overall. Thus, one form of atomic clock is the time it takes an electron to circle once around the nucleus. But all atomic processes are susceptible to change. The protons and electrons, being charged, are affected by the electric and magnetic properties of the vacuum of space. It can be shown that, as these vacuum properties become more intense, they inhibit all electric and magnetic processes, including atomic behavior. Conversely, if these vacuum properties were less intense than now, all electromagnetic processes would be faster and electric currents stronger. These effects would apply universally, not just to planet earth.

An Intrinsic Energy in Space: It is at this point that a 20th century discovery becomes important. It was found that there is an intrinsic energy in the vacuum of space or in a laboratory, even if that vacuum is cooled to absolute zero of temperature (about – 460 degrees F or -273 degrees C). For that reason, this energy is called the Zero Point Energy or ZPE. This energy arises from the expansion of space or the stretching of the fabric of space. As a simple illustration, we are aware that stretching a rubber band puts energy into the fabric of the rubber band, or inflating a balloon puts energy into the fabric of the balloon. In a similar way, the ongoing expansion of space puts more and more energy into the fabric of space. One concept of the fabric of space is shown here:

Here we have unusual shapes of rolled up extra dimensions forming the basic structure of space at exceptionally tiny scales. The point is that, using this diagram, an expansion of the fabric of space might be visualized as the distances between these shapes systematically increasing. In a similar way, the distances between the molecules in a rubber band increase as it is being stretched. The Importance of the Zero Point Energy: Be that as it may, the key thing to note here is that the electric and magnetic properties of the vacuum depend upon the strength of the Zero Point Energy (or ZPE). Thus, early in the history of the cosmos, when expansion had not lasted very long, the strength of the ZPE was low, and the electric and magnetic properties of the vacuum were not very strong either. This allowed all electric and magnetic processes to be faster. However, as the expansion went on, the ZPE built up and the electric and magnetic properties of the vacuum became more and more intense. This means that electric and magnetic processes, including those of atoms, would become increasingly inhibited as space expansion went on. On the specific matter of atomic clocks and their run-rate, a stronger ZPE meant the clocks were ticking more slowly, while a less intense ZPE meant that all atomic clocks ticked faster and marked off time more quickly. An analysis of the behavior of all forms of atomic clock, including radiometric dating, with ZPE behavior can be found in chapter 8 of the Monograph “Cosmology and the Zero Point Energy,” pp.298 – 318. Proof of Slowing Atomic Clocks: There is evidence for this behavior of atomic clocks. Astronomical observatories around the world have measured events for the various planets in orbital (gravitational) time simultaneously with atomic clock time. It can be show that orbital or gravitational time remains unaffected by ZPE changes as all varying terms cancel out in the equations. Thus, orbital or gravitational time (the time it takes a planet to go once around in its orbit, such as the earth’s year), is an unchanging quantity. As a result, when orbital events are measured in both atomic time and gravitational time, and graphed, the graph shows the atomic clock data for those events as dropping with time as the atomic clock slows down. A typical graph for such data is shown here for the planet Mercury. Here orbital (gravitational) time is graphed horizontally in years after 1900 AD, and atomic clock data is plotted vertically. The atomic clock line is dropping with orbital time in the period from 1910 to 1985. If the two clocks were running at the same rate, the two lines would both be horizontal and parallel.

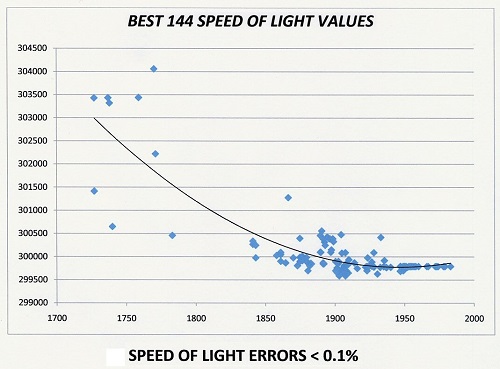

Atomic Clocks and Light: Since atomic clocks are all electromagnetic in character, they show this behavior because of the effect of the increase in the strength of the Zero Point Energy (ZPE). There are other quantities which are also electromagnetic in character, like the speed of light, which are similarly affected. This physical quantity is abbreviated by the letter “c.” In a similar way to atomic clocks, the speed of light, c, has also slowed down as space has become “thicker” with the Zero Point Energy. Scientists have measured values of this quantity going back over 300 years. The data were presented in “Atomic Constants, Light, & Time” by Norman and Setterfield in August 1987, and the final graph from a separate analysis of the data by Montgomery & Dolphin in 1992 is reproduced here:

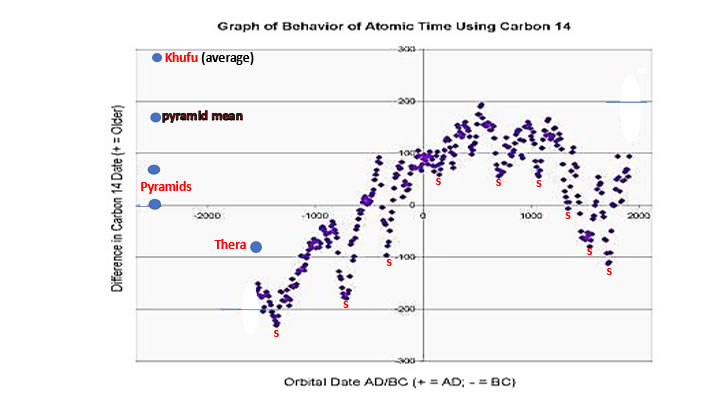

This slowing down of lightspeed was the subject of serious scientific discussion from the mid 1800’s until August 1941. After 1967, all experiments to measure lightspeed used atomic clocks for timing. But the rate of ticking of atomic clocks keeps synchronous time with the speed of light, so no change in “c” could be determined by that method after 1967. As a result, the speed of light value never changed and was declared an absolute universal constant in October 1983. Despite this development, it is possible, using other types of measurements, to pick up any changes in the speed of light as well as atomic clock rates. Since lightspeed and atomic clocks move synchronously, the difference in measurement between historical (or archaeological/orbital/gravitational) age, and the atomic age of the same event will show if atomic clocks and “c” are registering time more quickly or more slowly than historical time. Thus, if the atomic clock (or lightspeed) was faster in the past, then it would measure events as systematically too old compared with the historical or archaeological clock. This would happen because atomic clocks all marked off more time in a single orbital year than actually occurred since they were ticking faster. In turn, this meant that the strength of the Zero Point Energy (the ZPE) was lower back then than is currently the case. It should be noted that the converse is also true. So, a comparison between historical (orbital) dates and atomic clock dates tells us how the ZPE has behaved. The Most Sensitive Atomic Clock: There are several ways of determining the atomic age of historical or archaeological artefacts. However, there is one way which is more sensitive to changes in the ZPE than all the others. The reason is that this method is affected by two ZPE-controlled quantities instead of just one. These quantities are, first, the behavior of the ZPE itself, as expected. In addition, the effect of the ZPE on the strength of the earth’s magnetic field also affects this clock. The reason is that the earth’s magnetic field strength determines the quantities of the radioactive parent that are naturally produced for this clock. It has been shown (see Monograph, op. cit., Chapter 6, Table 1 and Figure 5) that the earth’s magnetic moment is inversely proportional to the square-root of the ZPE strength. Expressed another way, this means that the magnetic field strength varies with the ZPE in the same way as the square root of “c,” the speed of light. (Thus if the magnetic field varies by a factor of 3, then c will have varied by a factor of 9). The usual effect of the ZPE strength must therefore be coupled with the ZPE’s effect on the magnetic field for this particular clock. The result in that this clock ticks at a rate that not just proportional to the speed of light as all the others are, but to c^3/2. Thus, any changes in “c” (and hence inversely in the ZPE strength), are amplified by this particular form of atomic clock. This unusual sensitivity to ZPE effects, plus two special additional factors have led some to conclude that this whole system of measurement is unreliable. The first additional factor affecting this clock is solar behavior. This produces a variation around the actual value that is more or less rhythmic in character. This variation is dependent upon the sun’s 11, 22, and subsequent sunspot cycles up to the 440 year cycle and beyond. However, the data clearly display this effect, which can thus be allowed for as the pattern is apparent. The Data From Atomic Clock Behavior: It is at this point that the second additional factor enters the discussion and is the real cause for concern. The radiometric clock we are talking about here is carbon 14. Serious study by a number of scientists, including R.H. Brown of the Geoscience Research Institute and 2004 data from the Radiocarbon Institute emphasize that data from this clock can be accurately “corrected” to read real historical time as far back as 3500 BP. BP means Before Present, that is before 1950 AD. This date of 3500 BP thus corresponds to 1550 BC. However, earlier than this date, the “standard correction” procedure breaks down and is the source of many problems. It is open to criticism as it is based on tree-ring wiggle-matching techniques of wood of essentially unknown age. The limitation here is that the oldest continuous sequence of tree-rings only goes back to 1203 BC. All this is discussed in the Monograph (“Cosmology and the Zero Point Energy,” chapter 8, pp.311-314 and references therein). Therefore, the raw (uncorrected) carbon 14 data are taken as being accurate back to 1550 BC. Before that date, to un-tangle the web of “corrected” data compared with raw carbon 14 data needs a different approach. Here, then, are the accepted data back to 1550 BC:

Explaining the Data: These results now need some explanation. The horizontal line passing through the central zero position marks the rate of ticking of the atomic clock in 1950 AD. This is taken as the standard rate of ticking. If the rate of ticking of this atomic clock is faster than that rate, the plotted value will lie above that line. If the rate of ticking is slower than that standard rate, the plotted point will lie below that line. Orbital or historical dates AD lie to the right of the vertical line passing through the zero point. Dates BC are to the left of that vertical line and have a minus sign in front of them. It can be seen that, since a peak about 500 to 800 AD, the atomic clock has been slowing down consistently to 1950 AD. This is in accord with the speed of light data which shows “c” is also dropping over the latter part of this period. The data suggest there may be a rise in clock rate after 1950, but variation due to solar activity and industrialization is masking the true trend. The data were at a minimum close to 1400 BC and climbed consistently to the maximum about 800 AD. In that segment of the curve, the rate of ticking of the atomic clock reached the standard (1950 AD) rate sometime between 500 BC and 300 BC. The 9 low points marked with a red “S” are the times of solar minima. The last 3 going back from 2000 AD correspond with the periods called the Maunder Minimum around 1700 AD; the Sporer Minimum around 1500 AD and the so-called Little Ice Age starting 1350 AD. These three events occurred so close to each other because of a resonance in the sun’s cycle. The solar cycle variations are all relatively short-term in character, and largely account for the scatter in the data. But the long-term trend must be related to the behavior of the Zero Point Energy; as there is no other consistent explanation. In order to examine this in more detail, the data without the correction, and the behavior of this atomic clock prior to 1400 BC, must be considered. It is here that the recent pyramid data are valuable. On the chart above, 5 data points are inserted on the left as we go back in time; one is marked Thera, two are marked Pyramids, one is marked Khufu (average), and another one is labelled “pyramid mean.” Let us consider these.

Thera: The date of the Minoan Santorini eruption of the Thera volcano has been used as a marker for archaeological purposes across the Aegean and throughout its Mediterranean interconnections. The date is therefore of some importance. Archaeologists have established an elaborate cross-linked reference system for cultures across the region and established a chronology that seemed watertight for this event. That archaeological date was placed around 1500 BC, though Hoflmayer has argued cogently that the archaeological evidence is more consistent with a date of 1570 BC. This latter date is accepted here. In contrast, the atomic dates range from 3614 BP down to 3550 BP (that is 1664 BC down to 1600 BC). This discrepancy has been the source of an ongoing debate. In April 2006, Friedrich et.al. who obtained an atomic date of 1627-1600 BC for this event, stated in their Abstract in Science, 312, p.548, that “Our result is in the range of previous, less precise, and less direct results of several scientific dating methods, but it is a century earlier than the date derived from traditional Egyptian chronologies.” The conclusion is that the curve has now risen almost 100 extra years from its calibrated position in 1550 BC to that shown on this graph for Thera. Pyramids: Dynasty 4 in Egypt produced the Giza pyramids in a span of 85 years centered around 2550 BC. In 1984, the members of the David H. Koch Pyramids radiocarbon Project took 64 samples from pyramids and associated structures from Dynasties 3 to 5. Their conclusions were stated this way: “The dates, after dendrochronological calibration, averaged 374 years too early for the Cambridge Ancient History dates of the kings with whom the pyramids are identified.” In other words, the average data were 374 years above the calibrated curve and therefore in the position of the upper point above the word “pyramids” on the graph. The same research group in 1995 obtained samples from Dynasties 1 to 6. Thus, the scatter might be expected to be intrinsically greater, but a scatter was noted even for the same structure. These data gave results up to 350 years older than the historical dates for some structures. This is the lower point under the word “pyramids” on the graph. The conclusions of this two-fold study (1984 and 1995) were largely supported by the analysis of 450 samples by Bonani et al. which indicated that many Old Kingdom artefacts gave atomic dates around 300 years or more in excess of archaeological dates [Radiocarbon, 43 (3), 2001]. Therefore, these two data points are not spurious. Khufu: As stated at the beginning, the most recent accurate atomic date for Khufu’s pyramid lies between 3341 and 3094 BC, with an average date of about 3217 BC. That is an average of 667 years above the historical date of 2550 BC and gives us the data point labelled Khufu on the above graph. In fact, if the oldest date is taken instead of the average, then the point would be off the chart. The average of the two pyramid study results, plus the two limits of the Khufu data, give the point marked “Pyramid Mean.” Data Conclusion: The conclusion from these data is that, as we go back in time prior to 1550 BC, the curve of atomic time is climbing. A similar steep climb is recorded going back in time from about 1940 to say 1100 AD. The slope of the curve is similar. The atomic dates for pre-Dynastic structures may thus be expected to be very significantly older than is actually the case in orbital time. These pyramid data are therefore the key to the way atomic dates are behaving. They also give information about ZPE behavior.

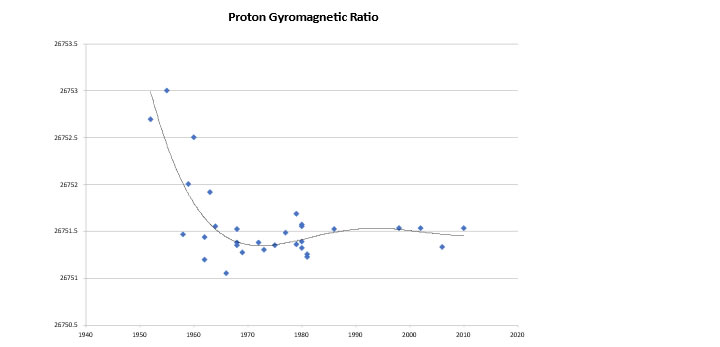

ZPE Behavior: The outstanding issue that now must be addressed is the behavior of the Zero Point Energy that this curve indicates. Basically, the curve shows an impressive drop in atomic clock rates down to about 1400 BC, followed by an oscillation. There is a suggestion that the curve may be rising again near 2000 AD, but we need other data. The ZPE behaves in reverse to this curve for atomic time (and “c”). This means that ZPE strength has climbed to a maximum about 1400 BC and then oscillated. That strength may be dropping again slightly since before 2000 AD. The best data available for this segment of time is the quantity called the proton gyromagnetic ratio. It is proportional to the square-root of “c” or inversely proportional to the square root of ZPE strength. That curve is here and shows the trend from 1950 to 2010 on a physical quantity that, until 2010 was unaffected by conventions and definitions:

These data indicate that the drop in atomic clock rates (and lightspeed) that was in evidence from about 1000 AD continued on until it bottomed out about 1965 to 1970 and oscillated slightly after that. This 1970 minimum is the secondary minimum after the primary (and deeper) one about 1400 BC. This would indicate that the ZPE, which behaves in an inverse manner, therefore rose to a secondary maximum about 1970 after its primary maximum around 1400 BC. These data indicate that the ZPE is now a gently oscillating quantity after a massive build-up from cosmic expansion. To discover why, we need to look at the behavior of the universe with time.

Universal Behavior & the ZPE: It is usually assumed that the initial expansion of the universe is ongoing, even right now. However, there are scientists who point to data which absolutely deny that – hydrogen cloud data for example. Consider the early universe; it was very much smaller initially, and objects were very close together. Then, as expansion set in, objects all became systematically farther apart. As expansion continued, the distance between objects increased, as in the above sketched examples. Hydrogen clouds have a special signature in their light spectra, which allows us to determine their distance and spacing. As a result, they are one illustration of these facts. Initially, they were crowded together, then, as the cosmos expanded, they became farther and farther apart. This continued to a redshift (z) distance of z = 1.6. At that point, the clouds stopped separating and have stayed roughly the same distance apart ever since. The indication is that cosmic expansion stopped around z = 1.6. However, the dynamics of the situation show that the ZPE continued to grow as turbulence in the fabric of space from the expansion continued and gradually died down. It is only after all turbulent energy had been converted into the ZPE that the ZPE reached its maximum value. Universal Behavior & the ZPE: It is usually assumed that the initial expansion of the universe is ongoing, even right now. However, there are scientists who point to data which absolutely deny that – hydrogen cloud data for example. Consider the early universe; it was very much smaller initially, and objects were very close together. Then, as expansion set in, objects all became systematically farther apart. As expansion continued, the distance between objects increased, as in the above sketched examples. Hydrogen clouds have a special signature in their light spectra, which allows us to determine their distance and spacing. As a result, they are one illustration of these facts. Initially, they were crowded together, then, as the cosmos expanded, they became farther and farther apart. This continued to a redshift (z) distance of z = 1.6. At that point, the clouds stopped separating and have stayed roughly the same distance apart ever since. The indication is that cosmic expansion stopped around z = 1.6. However, the dynamics of the situation show that the ZPE continued to grow as turbulence in the fabric of space from the expansion continued and gradually died down. It is only after all turbulent energy had been converted into the ZPE that the ZPE reached its maximum value.

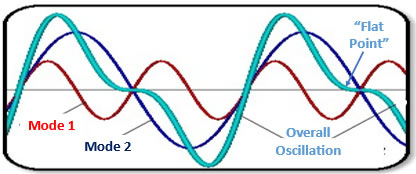

The persisting turbulence is strong enough to overturn other large aircraft, and is a similar problem in flight. Similarly, in the cosmic case, there was a long persistence time for the turbulence in the fabric of space after space expansion ceased. Until it had decayed and died down completely, the ZPE continued to build. The Oscillation: Once the ZPE had built to its maximum, the question arises as to why its strength should vary in the manner that the data from the pyramids and elsewhere indicate it has. The initial impression is that, once the cosmos has reached its maximum size, it would stay there. However, we are dealing with a dynamic entity where various forces are at work. In March 1993, the astronomers Narlikar and Arp demonstrated in the Astrophysical Journal, 405:1, pp.51-56, that a static cosmos with matter in it would be stable and not collapse despite all the forces acting, including gravity. The one proviso was that the cosmos must oscillate slightly in various modes around its new mean position. This meant the overall form of the oscillation might be complex rather than simple. The sort of behavior is illustrated here:

In this diagram, there are two different modes of oscillation – Mode 1 in red and Mode 2 in dark blue. These oscillation modes may also be considered as being similar to two different wave-forms in an ocean - one waveform from the tide, the other from the wind. When these two modes are combined in one body (as we are considering for the cosmos or an ocean), then the resultant oscillation takes an overall or combined oscillation form as shown by the teal-colored curve. Notice that this curve has “flat points” where Mode 1 and Mode 2 interact in such a way that they cancel out. The teal-colored curve has similarities to the Carbon 14 curve with pyramid data superimposed, and the curve for the proton gyromagnetic ratio. Thus the “flat point” in the speed of light and carbon 14 curves may be explicable in these terms. What the Oscillation Means for the ZPE: This oscillation curve with the atomic clock (carbon 14) data indicates is that at the minimum positions, the strength of the ZPE was at a maximum. The converse also holds. How is this possible? Consider a more or less spherical cosmos in its average position in which the ZPE strength had built up to a maximum after the expansion had ceased, and all turbulence had died down. This universe is now oscillating inwards and outwards in a gentle fashion in two or more modes. When the oscillation brought the cosmos into a minimum size, the same total amount of the ZPE was confined in a smaller volume, so its strength increased temporarily. Then, when the cosmos expanded out, past its average position, to its maximum size, the same amount of ZPE was held in a larger volume. As a result, the ZPE strength was at a temporary minimum. In this way, the behavior of the universe is reflected in the varying strength of the ZPE. Thus, Narlikar and Arp’s analysis has been proven correct by these new pyramid data for the atomic clock. Furthermore, the pyramid data have indirectly pointed to the gently oscillating behavior of the universe. Final Summary & Conclusion:

|

.jpg)